CYRK... Polish Posters In The News:

Flying in Style: Vintage Airline Posters

By ALEXANDRA WOLFE Published from the magazine issue dated July 17, 2015 |

Air travel wasn’t always such an unpleasant chore. A hefty new coffee table book, “Airline Visual Identity” (Callisto Publishers, $400) by Matthias Hühne, showcases airline advertisements from 1945 to 1975, an era when flying was actually fashionable. The spirit of tÂhe posters changed over the decades, along with the advertising industry itself. In the early 1940s, the designs were more romantic, holding out air travel as a luxury experience. As the ad industry gained momentum in the 1960s and air travel expanded, the posters became more sleek and self-consciously modern. These days, stylish airline ads seems to have gone the way of free checked luggage. “Today the airlines really don’t put as much of an emphasis on their design,” says Mr. Hühne, thanks to airline deregulation in the 1970s. “Before, people picked an airline more because of the message…and today they just pick an airline because of the price.”

Air travel wasn’t always such an unpleasant chore. A hefty new coffee table book, “Airline Visual Identity” (Callisto Publishers, $400) by Matthias Hühne, showcases airline advertisements from 1945 to 1975, an era when flying was actually fashionable. The spirit of tÂhe posters changed over the decades, along with the advertising industry itself. In the early 1940s, the designs were more romantic, holding out air travel as a luxury experience. As the ad industry gained momentum in the 1960s and air travel expanded, the posters became more sleek and self-consciously modern. These days, stylish airline ads seems to have gone the way of free checked luggage. “Today the airlines really don’t put as much of an emphasis on their design,” says Mr. Hühne, thanks to airline deregulation in the 1970s. “Before, people picked an airline more because of the message…and today they just pick an airline because of the price.”

A Visit With Broadway Master John Kander

By STEFANIE COHEN Published from the magazine issue dated April 22, 2015 |

On one entire wall of John Kander ’s Manhattan townhouse hang 14 posters: all the composer’s Broadway shows, in chronological order, from 1965’s “Flora the Red Menace,” to 1966’s “Cabaret,” to 2010’s “The Scottsboro Boys.”

On one entire wall of John Kander ’s Manhattan townhouse hang 14 posters: all the composer’s Broadway shows, in chronological order, from 1965’s “Flora the Red Menace,” to 1966’s “Cabaret,” to 2010’s “The Scottsboro Boys.”At 88, Mr. Kander needs to make room for one more. “The Visit,” starring Chita Rivera and Roger Rees, opened on Thursday at the Lyceum Theater. The musical is based on a 1956 play by Friedrich Dürrenmatt about what happens when the wealthiest woman in the world (Ms. Rivera) returns to her impoverished Swiss hometown to exact revenge on her first love (Mr. Rees). The show is the last by Mr. Kander and his longtime writing partner, lyricist Fred Ebb, who died in 2004.

Mr. Kander says a producer brought the play to him in the late 1990s, and the composer immediately felt that he could express through song, in a way the play does not, the love between the two elderly main characters.

“You don’t just take any story and put songs in it,” he says. “The relationship between the two people was the hook for us.”

The show, directed by John Doyle, is dark and spare, the plot disturbing. But Kander and Ebb, one of the most successful songwriting duos in the history of Broadway, have always been drawn to darker material. “Cabaret,” for instance, tells the story of two couples against the backdrop of the rise of the Third Reich. “Chicago” is a cynical look at the justice system and celebrity. And “The Visit”—which was written, Mr. Kander says, as an allegory for Swiss duplicity during World War II—is no exception. The duo’s most famous song, however, is the upbeat “New York, New York,” written for the 1977 film of the same name, directed by Martin Scorsese.

Mr. Kander, who himself has a sunny disposition, says he and “Freddy,” as he calls Mr. Ebb, weren’t particularly attracted to dark themes, just subjects that are rich.

“We liked subjects that bring with them color, passion and questions,” he says. “That’s what makes me want to write.”

When he and Mr. Ebb began a new project, they would sit in a room with the book writer—in the case of “The Visit,” Terrence McNally —and “talk and talk and talk and talk,” he says, to make sure that when they started writing, they all had the same idea of who the characters were. Often, Mr. McNally wrote a speech that Mr. Kander and Mr. Ebb stole for a song.

“They cannibalized my words all the time,” says Mr. McNally, who has worked on three Kander and Ebb shows. “But I take it as a compliment when lines of mine become lyrics.”

Mr. Kander says he used to pop over to Mr. Ebb’s house at around 10:30 each morning—the two lived just four blocks away from each other on the Upper West Side—and worked until the late afternoon. They would write 50 or so songs, or snippets of songs, per show before hitting on the right ones. “We wrote fast but would throw away fast, too,” he says. “You know what works when you hear it.”

The two began their work in the theater when shows were less costly and a flop didn’t end a career. “We were part of the last generation that was allowed to fail,” says Mr. Kander. Hal Prince, who produced Kander and Ebb’s “Flora the Red Menace,” told the team that no matter what, the three would meet the day after “Flora” opened and talk about their next show. “Flora” was not a hit—the New York Times called the show “a fable for infants.” As promised, they met the next day and started talking about their next piece—which turned out to be “Cabaret,” a show that has had three successful Broadway runs, including one that just closed, and is produced all over the world.

The Kander-Ebb team and Mr. McNally began writing “The Visit” in the late ’90s, and it premiered at the Goodman Theater in Chicago in 2001. After Mr. Ebb died, friends of Mr. Kander’s asked if he planned to keep working on the shows he and Mr. Ebb had begun, and he decided he would. The score to “The Visit” was complete, and after a 2008 production in Arlington, Va., director John Doyle was hired to streamline the show. That version is now on Broadway.

The score and orchestration have undergone some changes under Mr. Doyle’s direction. “I told John I wanted it to feel like a European musical with a Germanic quality,” Mr. Doyle says. “I didn’t want it to feel like a Broadway musical.” One song, “Yellow Shoes,” does have a traditional Broadway sound, but other songs feature accordion and zither, instruments not often heard in Times Square.

Mr. Doyle says Mr. Kander showed no ego when it came to changing the tone of the work. But the lyrics, for the most part, are the same. “John is very respectful of Fred’s work,” says Mr. Doyle. “We didn’t start changing them just because Fred is no longer here.”

Looking at his wall of posters, Mr. Kander begins telling stories about his past. “The Rink,” starring Chita Rivera and Liza Minnelli, featured Ms. Minnelli in a serious role. She took it, he says, because she wanted a role with not one sequin in it. “Unfortunately, no one wanted to see Liza without sequins,” he says.

Mr. Kander recalls that, during rehearsals for “Chicago,” Bob Fosse had a massive heart attack: “When he came back to work he was still brilliant, but he was a darker person.”

Then there was the time during rehearsals for 1981’s “Woman of the Year,” with Lauren Bacall, when Mr. Ebb was waiting for a call from the actor James Coco. When the phone rang, and Mr. Ebb heard a deep voice on the other end. He said, “Hi, Jimmy!” Unfortunately, it was Ms. Bacall. They all called her Jimmy for the rest of the run.picture really could speak a thousand words.

Cowboys vs. Communism

By Alexandra Wolfe Published from the magazine issue dated February 15-16, 2014 |

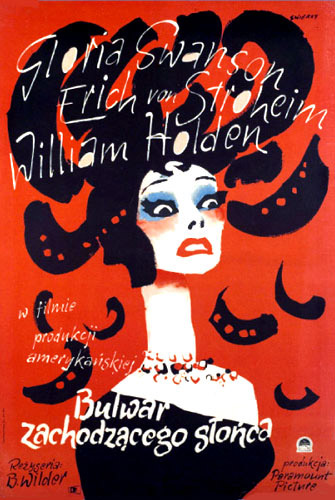

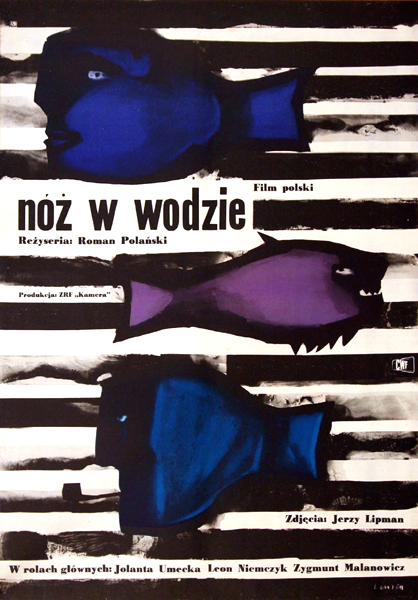

American Western film posters may not seem like they would have been an obvious reflection of dissent in communist-era Poland, but many of the Polish Poster School's vintage images contained hidden political messages. A new exhibit at the Denver Art Museum, starting Sunday, showcases 28 posters from the 1950s to the 1980s in which Western film icons such as the six-shooter, the cowboy and the American Indian often were used as subversive commentary on the Soviet-backed communist regime. The poster for "The Missouri Breaks," for example, shows a cowboy's head growing from the ground with vegetation sprouting from his hat—an allusion to the oppression suffered by the Polish people. "Film posters were one of the few modes considered not to be a threat," says curator Darrin Alfred, so they weren't subject to censorship, like other art forms. The exhibit runs through June 1

American Western film posters may not seem like they would have been an obvious reflection of dissent in communist-era Poland, but many of the Polish Poster School's vintage images contained hidden political messages. A new exhibit at the Denver Art Museum, starting Sunday, showcases 28 posters from the 1950s to the 1980s in which Western film icons such as the six-shooter, the cowboy and the American Indian often were used as subversive commentary on the Soviet-backed communist regime. The poster for "The Missouri Breaks," for example, shows a cowboy's head growing from the ground with vegetation sprouting from his hat—an allusion to the oppression suffered by the Polish people. "Film posters were one of the few modes considered not to be a threat," says curator Darrin Alfred, so they weren't subject to censorship, like other art forms. The exhibit runs through June 1

![]()

The Writing on the Wall

|

By Isia Jasiewicz

Published Jul 24, 2009 From the magazine issue dated Aug 3, 2009 |

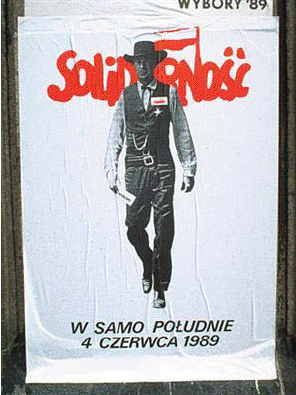

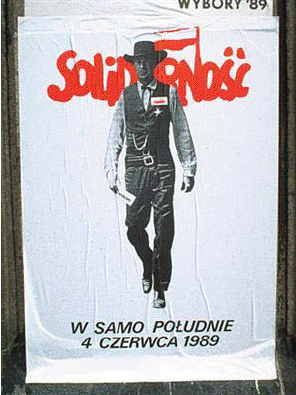

It was a Sunday morning in 1989,

and Gary Cooper was all over

Warsaw. Nearly 10,000 posters,

plastered around the city at daybreak,

bore the image of the marshal from

the 1952 Western High Noon. His

photograph was black and white, save

for the red Solidarity logo placed on

his chest, and he carried a paper

ballot in place of a pistol. The poster's

inscription was simple: IT'S HIGH

NOON, JUNE 4, 1989.

That paper sheriff was on a mission:

to encourage Poles to vote for

Solidarity in that day's parliamentary

elections. In the Western, the hero

always wins; in the elections,

Solidarity secured a landslide victory,

and the High Noon poster became an

emblem of triumph and new

beginning. Yet the poster itself marked an ending. It was the last great work

of the Polish Poster School.

Half a century before Twitter became the medium of choice for underground

communications in Iran, artistically innovative Poles used the power of

images to slip subversive messages past the communist watchdogs. In an

age when "print" means "old," and visual appeal takes a back seat to speed,

it's hard to believe what a powerful weapon lithography could once be.

Twenty-four posters from the heyday of the Polish school are on view at New

York's Museum of Modern Art until November. The works, clustered together

as they would have been on a poster kiosk in Warsaw, chronicle a movement

that actually benefited from the oversight of the communist regime. Posters

advertising plays, films, circuses, and exhibitions were subject to strict

control, but they also received state funding. Censorship also provided a

strangely nurturing environment for creativity, especially in the way artists

borrowed from surrealism and expressionism to develop a language of

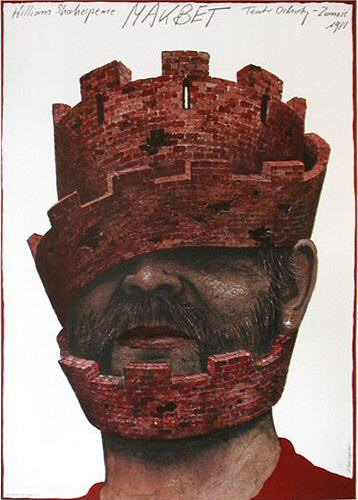

metaphor. In one poster advertising a 1981 production of Macbeth, the

king's face appears trapped in a kind of brick bandage resembling a castle.

His eyes are obscured, his jaw locked in place. To the censor, it showed a

face with a castle; to the viewer, it could speak volumes about the blinding,

mind-numbing danger of power.

It's been 20 years since Cooper's marshal marched into Warsaw, leaving the

country—and its posters—changed forever. Poles remembered his influence

on the anniversary of the election this year by displaying an oversize reprint

of the poster on Warsaw's Palace of Culture. But today, state support for

artists is gone, and sales-driven, artless advertising is king. In Poland (as in

the United States), visual culture is saturated with pop-up ads and all-too-

obvious sales slogans. It's nearly impossible to find socially compelling

commercial art. Maybe the Polish Poster School can take us back to that high

noon, when a picture really could speak a thousand words.

© 2009

It was a Sunday morning in 1989,

and Gary Cooper was all over

Warsaw. Nearly 10,000 posters,

plastered around the city at daybreak,

bore the image of the marshal from

the 1952 Western High Noon. His

photograph was black and white, save

for the red Solidarity logo placed on

his chest, and he carried a paper

ballot in place of a pistol. The poster's

inscription was simple: IT'S HIGH

NOON, JUNE 4, 1989.

That paper sheriff was on a mission:

to encourage Poles to vote for

Solidarity in that day's parliamentary

elections. In the Western, the hero

always wins; in the elections,

Solidarity secured a landslide victory,

and the High Noon poster became an

emblem of triumph and new

beginning. Yet the poster itself marked an ending. It was the last great work

of the Polish Poster School.

Half a century before Twitter became the medium of choice for underground

communications in Iran, artistically innovative Poles used the power of

images to slip subversive messages past the communist watchdogs. In an

age when "print" means "old," and visual appeal takes a back seat to speed,

it's hard to believe what a powerful weapon lithography could once be.

Twenty-four posters from the heyday of the Polish school are on view at New

York's Museum of Modern Art until November. The works, clustered together

as they would have been on a poster kiosk in Warsaw, chronicle a movement

that actually benefited from the oversight of the communist regime. Posters

advertising plays, films, circuses, and exhibitions were subject to strict

control, but they also received state funding. Censorship also provided a

strangely nurturing environment for creativity, especially in the way artists

borrowed from surrealism and expressionism to develop a language of

metaphor. In one poster advertising a 1981 production of Macbeth, the

king's face appears trapped in a kind of brick bandage resembling a castle.

His eyes are obscured, his jaw locked in place. To the censor, it showed a

face with a castle; to the viewer, it could speak volumes about the blinding,

mind-numbing danger of power.

It's been 20 years since Cooper's marshal marched into Warsaw, leaving the

country—and its posters—changed forever. Poles remembered his influence

on the anniversary of the election this year by displaying an oversize reprint

of the poster on Warsaw's Palace of Culture. But today, state support for

artists is gone, and sales-driven, artless advertising is king. In Poland (as in

the United States), visual culture is saturated with pop-up ads and all-too-

obvious sales slogans. It's nearly impossible to find socially compelling

commercial art. Maybe the Polish Poster School can take us back to that high

noon, when a picture really could speak a thousand words.

© 2009

MOMA's 'Polish Posters, 1945-89'

May 27, 2009

Abandoned for the Web's glitz and neglected long before that, graphic design in this country has reached such a despairing state of utilitarian blandness that, with few exceptions, it now seems little more than an afterthought. A reminder, then, of what might be the art form's most brilliant period—the Polish poster movement—should be cause for celebration. The trouble is, MOMA has crammed this exhibit into a corner, displaying many of the posters far above eye level and presenting the excellent documentary on the subject, Freedom on the Fence, at a virtually inaudible volume—only confirming the lowly status of graphic design.

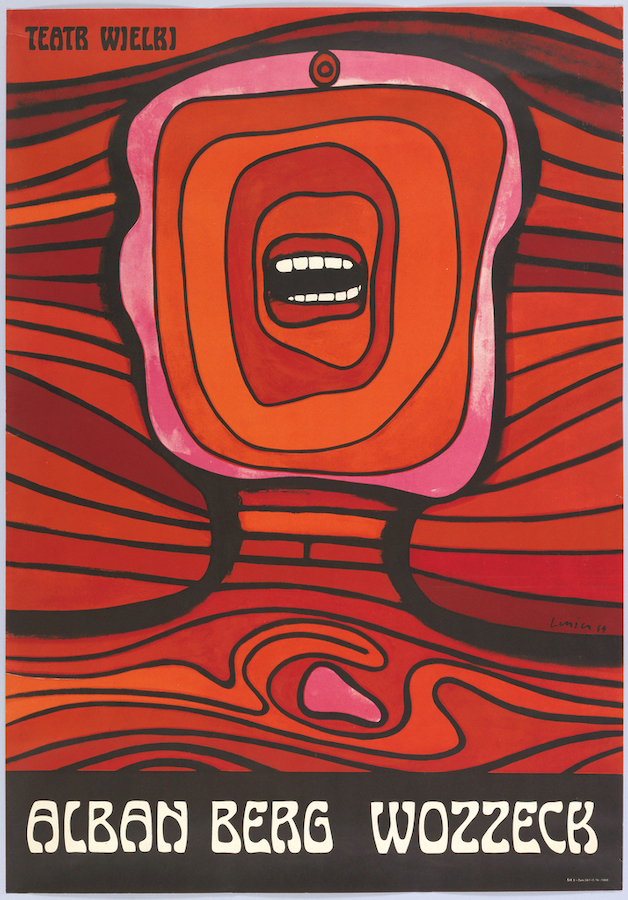

Abandoned for the Web's glitz and neglected long before that, graphic design in this country has reached such a despairing state of utilitarian blandness that, with few exceptions, it now seems little more than an afterthought. A reminder, then, of what might be the art form's most brilliant period—the Polish poster movement—should be cause for celebration. The trouble is, MOMA has crammed this exhibit into a corner, displaying many of the posters far above eye level and presenting the excellent documentary on the subject, Freedom on the Fence, at a virtually inaudible volume—only confirming the lowly status of graphic design.But the genius manages to shine anyway. Forced to work under Communist censorship, Polish designers distilled their ideas for film, theater, and opera advertisements into biting metaphors that often doubled as political protest or reflections of the collective anxiety. Jan Lenica's hallucinatory poster for Alban Berg's intensely charged opera Wozzeck features a screaming mouth lost in a red vortex; Andrzej Pagowski wraps Macbeth's head in a brick castle, while Wiktor Gorka's bold composition promoting the American western The Tall Men places the shimmering silhouettes of dueling cowboys against a sky of desert orange. Mieczyslaw Gorowski, another great designer, remembers the posters, ubiquitous at the time, as being "flowers in the empty space." Even after the fall of Communism, they're still blooming.

MOMA, 11W 53rd, 212-708-9400. Through November 30

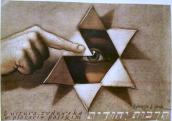

Jewish Polish Posters at JCC

November 29, 2006

It is a little known fact in the Jewish world that Poland is famous for its artistic posters. At the annual art and poster fairs held in New York City there is always a very large and impressive collection of fine art posters from Poland.

It is a little known fact in the Jewish world that Poland is famous for its artistic posters. At the annual art and poster fairs held in New York City there is always a very large and impressive collection of fine art posters from Poland.

Surprisingly, a high number of them have Jewish themes. Last week an exhibit of nearly 100 Jewish-themed Polish posters was opened at the JCC of Manhattan.

In a talk given at the gala opening of the exhibit, Donald Mayer spoke about the long history of Polish poster printing and how the art form always contained a Jewish flavor due to the fact that Jewish culture was so entwined with Polish culture as a whole.

"Even after the Shoah, when there were hardly any Jews left in Poland," Mayer explained, "there was not a significant drop in Jewish poster art."

There are many examples of Yiddish theater posters, as well as posters for books, films and cultural events.

Most of the posters in the exhibit were printed after the Shoah, and therefore many have a melancholy look to them. Many are in stark colors with broken or twisted imagery, depicting the mood of the subject.

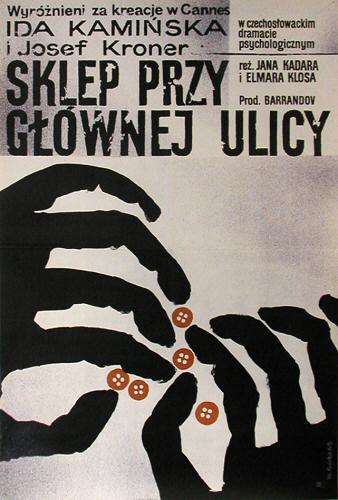

The poster for "A Shop On Main Street" by Wiktor Gorka, 1965, was printed for the Academy-Award-winning film starring an aging Ida Kaminska. It shows shadows of a pair of old hands reaching for buttons on a beige background. This poster is an example of what was produced for the foreign market, as the film was produced by a Czech production company. Some other well-known films are represented at the exhibit are "Cabaret" and "Europa Europa."

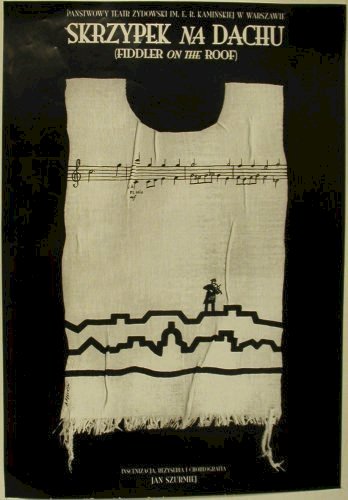

Music and opera are also popular poster topics. There is a whole grouping of posters relating to "Fiddler on The Roof" and other familiar stories that have been put to music, such as "Nabuco," Verdi's opera telling the story of the Babylonian exile, and "La Juive."

Another popular subject for poster art, especially after the fall of communism in 1989, is the Jewish Cultural Festival held each year in Krakow. For 18 years now, exceptional Jewish-themed posters have been produced for this popular festival held annually in Krakow at the end of June. While the Krakow festival features new posters each year, the Jewish festival in Warsaw reuses the same posters each year but changes the color scheme for every festival.

Most of the posters were printed on poor paper, as posters are considered ephemera - printed works not expected to last very long. The posters at the exhibit have been backed with linen for preservation, and some are even signed by the artist.

The exhibit by Ylain and Donald Mayer of Contemporary Posters can be viewed at the JCC of Manhattan, 334 Amsterdam Ave. at 76th Street, until January 17, 2007.

All the posters are for sale.

The Tentacles of Jewish Roots

By Carolyn Slutsky

November 22, 2006

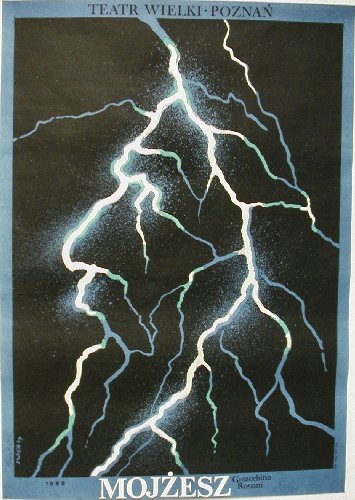

Bolts of lightning pierce the black background and take the form of

a human face in profile. The face looks regal: a craggy nose,

wizened eyes.

Bolts of lightning pierce the black background and take the form of

a human face in profile. The face looks regal: a craggy nose,

wizened eyes.The poster depicts Moses, and was created by Waldemar Swierzy to promote a 1989 production by the Great Theater of Poznan of "Moses in Egypt," an opera by Rossini.

The rendition of Moses is one of nearly 100 posters from the Polish School of Posters on display in a show that opened Monday and runs through Jan. 17 at the Laurie M. Tisch Gallery at the Jewish Community Center in Manhattan. It is the largest mounting of Polish poster art ever in New York, and all the placards on display in the bustling JCC lobby — where children, parents, nannies and anyone can view them — are for sale.

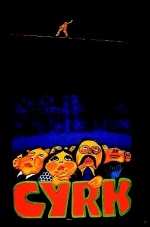

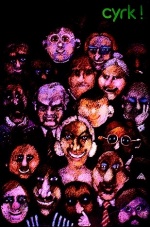

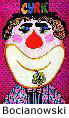

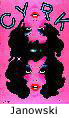

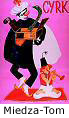

Posters have a long history in the Polish artistic tradition. During communism, all art was sponsored — and censored — by the government, and though some creations were tools of propaganda, artists from the media of painting, drawing, sculpture and photography were also paid well to design artistic announcements for plays, films and musical events. Colorful posters depicting Cyrk, the Polish circus, flourished, with more than 300 designs throughout the communist era.

Though poster art, characterized by bold colors and hand lettering, was a staple of design throughout the Eastern bloc and Europe, Poland specialized in posters portraying Jewish themes.

"Jewish and Polish culture were intertwined," said Karen Sander, senior director of arts and culture adult programs at the JCC, explaining why Polish artists and the government so readily embraced Jewish themes. The posters, she said, expressed "the tentacles of Jewish roots" in Polish society.

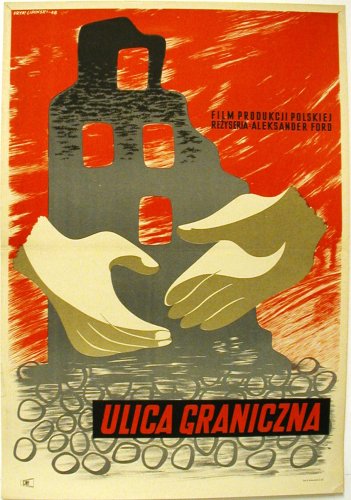

The posters in the JCC show reflect this attention to Jewish

subjects. One poster by Eryk Lipinksi promotes a 1948 film

called "Border Street," which deals with the Warsaw Ghetto. The

poster shows two hands almost meeting in front of a backdrop of

rubble and stones. Banned in Poland for a time, the film and poster

were later re-released. A series of five posters is devoted to

different productions of "Fiddler on the Roof," a show that

captivated Polish audiences when it was broadcast on national

television under communism in the 1980s, and that still runs in

repertory in Krakow today. Other posters announce performances

of "The Dybbuk" by Solomon Anski and Isaac Bashevis Singer's "The

Magician of Lublin," as well as the American works "Sweet

Charity," "Death of a Salesman" and "Cabaret."

The posters in the JCC show reflect this attention to Jewish

subjects. One poster by Eryk Lipinksi promotes a 1948 film

called "Border Street," which deals with the Warsaw Ghetto. The

poster shows two hands almost meeting in front of a backdrop of

rubble and stones. Banned in Poland for a time, the film and poster

were later re-released. A series of five posters is devoted to

different productions of "Fiddler on the Roof," a show that

captivated Polish audiences when it was broadcast on national

television under communism in the 1980s, and that still runs in

repertory in Krakow today. Other posters announce performances

of "The Dybbuk" by Solomon Anski and Isaac Bashevis Singer's "The

Magician of Lublin," as well as the American works "Sweet

Charity," "Death of a Salesman" and "Cabaret."

Throughout communism, Poland always maintained a national Jewish theater, with plays in Yiddish attended largely by Polish audiences, and for each play at the E. R. Kaminski National Jewish Theater, an artist was commissioned to compose a poster.

"Jewish culture is Polish culture, and Polish culture is Jewish culture," said Ylain Mayer who, with her husband Donald, is the curator of the exhibition. The two collect and sell art through their company, Contemporary Posters, and have long been captivated by the Polish School of Posters placards that so delicately and forcefully treat Jewish themes.

While poster art declined after the fall of communism, when the government no longer sponsored artists, Jewish poster art continued, and Poland today is one of the few areas in which many artistic posters still thrive.

Today, Jewish culture festivals in Krakow and Warsaw commision artists to create grand posters for their annual events, and exhibitions, theater and musical acts are still announced, though sometimes more commercially, through placards in the tradition of the Polish School of Posters.

The JCC exhibit runs in concert with a series of programs co- presented by the Polish Cultural Institute focused on "the complexity of the Polish-Jewish culture and relationship," said Sander. Other programs will include "The Last Escape," a Wroclaw Puppet Theater show based on the writings of Polish-Jewish author Bruno Schulz which runs Nov. 18-19; a screening of the Andrzej Wajda film "Korczak" about the doctor and writer who ran an orphanage in the Warsaw Ghetto and died with his children in Treblinka; and an upcoming class on the Jews of Poland.

For the Mayers, the show and the posters themselves are an opportunity to engage with the 800-year strong Jewish history that was intricately tied to the Polish milieu in which the posters were created.

Said Ylain Mayer: "We hope to improve Polish-Jewish relations and dialogue."

Polish Theater Posters That Provoke

By J.S.

MARCUS

September 8, 2006

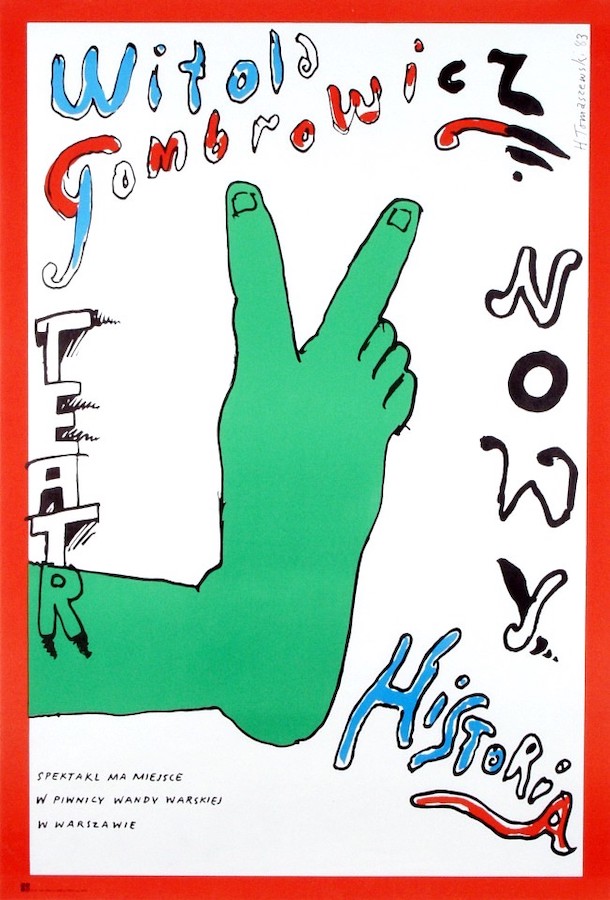

The year 1983 was a dark one in Warsaw. The

Communist-controlled government had cracked down on Lech Walesa's 1981

Solidarity movement, and many of its leaders and followers were in prison

or in exile. But a subversive splash of color brought life to Warsaw's

streets that year -- a poster announcing a new theater production of

"Historia," or "History," by Poland's sardonic 20th-century master, Witold

Gombrowicz, first uncovered after the author's death in 1969.

Featuring a preposterous foot with two finger-like toes

held up in a "V," the poster was a complex show of defiance. With its

cartoonish surrealism, it seemed to be a call for peace as well as for

victory and announced that freedom, like the play itself would rise from

the dead.

Designed by a master of Polish graphic art, Henryk

Tomaszewski, the "Historia" poster is one of thousands of remarkable

posters produced during the country's decades of Communist rule. Made to

commemorate or advertise cultural events, they appeared at a time when

there was otherwise little or no advertising.

The posters -- which managed to slip under the censors'

radar, as they were more concerned with explicit signs of protest --

relieved the gloom of postwar Polish streets, which remained scarred for

decades. "The artists used words like 'flowers' to describe their

posters," says Andrea Marks, associate professor in the art department at

Oregon State University and founder of "Freedom on the Fence," an online

documentary on the history of Polish posters (oregonstate.edu/freedomonthefence).

The talent of the artists involved and the nurturing personality of

Tomaszewski came together to make this movement remarkable, she says.

Known as the "Polish School" of poster art, the movement

began after the death of Soviet premier Joseph Stalin in 1953 allowed for

a thaw throughout the Soviet bloc. Characterized by highly unusual, often

grotesque, imagery, the school flourished until the fall of Communism in

1989. Many experts agree that the artistic high point was reached in the

1960s, when the movement's name came into use, and graphic artists from

around Europe made pilgrimages to Poland to study with Tomaszewski, then a

professor of design at Warsaw's Academy of Fine Arts.

In recent years, the Polish poster school has established

itself as a small, but growing niche market for collectors, who may have

discovered the movement while traveling in Eastern Europe, or by browsing

and buying on the Internet. "The past year has been the best I have ever

had in terms of Polish theater posters," says Martin Rosenberg, a Santa

Fe, New Mexico, poster dealer and curator (http://www.mrposter.com/).

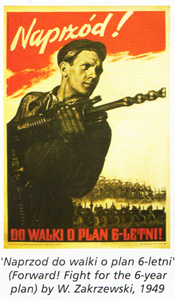

In contrast to the official style of socialist realism in painting and sculpture and the graphic style of official government posters, the posters created by artists in the Polish School of Poster movement functioned as sly commentaries on Poland's political situation and provided opportunities for individual expression, says Maria Kurpik, director of the Wilanow Poster Museum in Warsaw (http://www.postermuseum.pl/).

For collectors now, Polish film posters are a bigger draw (in March, Waldemar Swierzy's 1973 poster for the movie "Midnight Cowboy" sold for £960 ($1,810), double its estimated value in 1996, says Sarah Hodgson, head of the department for popular entertainment at Christie's in London). Nevertheless, Polish theater posters hold a special place for collectors, says Donald Mayer, whose New York gallery and Web site, Contemporary Posters, specializes in Polish poster art (https://www.contemporaryposters.com/). Mr. Mayer and his wife, Ylain, started out collecting abstract expressionist art from the 1950s and 1960s, which led to an interest in Polish poster art frm the same period. Like their customers, the Mayers were drawn to the dramatic stories behind many of the theater posters. "It's the history as well as the art that fascinates us," Mrs. Mayer says.

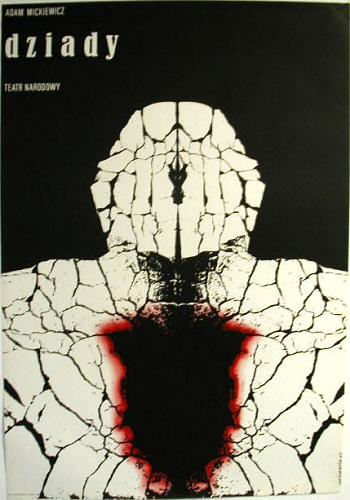

For instance, "Dziady," or "Forefathers," a 19th-century play by Adam Mickiewicz, is a humanistic plea for freedom that was banned during Poland's Stalinist years. In late 1967, a revival at Warsaw's Teatr Norodowy came under the eye of the censor for drawing too close a connection between the czarist tyrants of the play and Poland's Communist government. In March 1968, after the production was banned, students marched in protest from the theater to a Mickiewicz memorial, triggering a wave of national unrest. The poster, designed by Roman Cieslewicz, an émigré working at that time in France, was hardly seen on the streets, but it proved prescient. Featuring a stone man about to crumble into pieces, with a hole where his heart should be, the poster brilliantly dramatizes the predicament of a society on the brink of collapse. At Contemporary Posters, the poster is priced at $375.

In a famous poster designed in 1962 by Franciszek Starowieyski for Friedrich Dürrenmatt's play, "Frank V," a skull is grafted onto a baroque palace, and the cavity where the nose would have been is an open window. (It is priced at €400 ($512) at the Polish Poster Gallery, www.poster.com.pl, in Warsaw's Old Town.)

Uwe Loesch, a Düsseldorf poster artist, whose work -- like Tomaszewski's -- is in the design collection at New York's Museum of Modern Art, says such strange and even morbid figures are one of the features that distinguish the Polish theater posters. "There are historic reasons for the monsters," says Mr. Loesch, who sees cathartic power in the images. "Poland was completely destroyed after the war. Most of the concentration camps were in Poland. Then came the dictatorship of the Poland's archenemy, Russia. The Poles were traumatized."

After Communism's fall, the streets of Polish cities filled with Western advertising, and with Western tourists. Piotr Syrycki, an employee at the Polish Poster Gallery, credits Western tourists with helping to rediscover the Polish poster school. Increased travel by Poles also has played a role. Ms. Marks learned about the movement from books brought by a student who came to Oregon from Warsaw as part of an exchange program in 1997. "As soon as I saw these books, I was floored," she says.

Originally produced in print runs of around 3,000, Polish theater posters from the Communist era were printed on low-quality paper. The Mayers put the fragile pieces on a linen backing. Their advice to collectors is to rely on reputable dealers to distinguish between originals and reprints. It also is important to look closely at the texture of the paper, the color of the images and the publisher logos.

Jan Lenica's famous poster for the opera "Wozzeck" is at the high end of prices for the theater-poster genre. Inspired by Alban Berg's modernist opera, the poster recalls the expressionist styles of the 1920s, when Berg's opera premiered, while the colors anticipate the psychedelic hues of the 1970s. The poster won a gold medal for "posters promoting culture and art" at Warsaw's first International Poster Biennial in 1966, at the height of the Polish poster school. The original 1964 version now costs €1,200 at the Polish Poster Gallery and $850 at Contemporary Posters in New York. However, a "Historia" poster, when in stock could be bought for a modest €120-€150, the Polish Poster Gallery estimates.

The 20th Poster Biennial, held at the Wilanow Poster Museum, is on now through Sept. 17. This year's most acclaimed theater poster, awarded a prize at the Biennial by the Polish Stage Artists' Union, is by Lech Majewski, a professor of graphic arts at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts. His poster for "Balladyna," a mid-19th century Romantic drama by Juliusz Slowacki, features a stencil-like image of a woman and a black outline of a knife. It recalls the menacing, figurative tradition of the Polish school, but uses new typefaces and color schemes.

"It is important for the graphic designer to look back as well as look into the future," Mr. Majewski says.

Funds Target Art as New Asset Class --- Fernwood Art Investments, ABN Amro Aim to Create Portfolios of Masterpieces

By Jeff D. Opdyke

November 10, 2004

And so will investors.

Art is increasingly seen these days as not just a pretty picture but also as a potentially attractive investment. A variety of major banks and other outfits are looking to art not just for its aesthetic value, but also as an alternative asset class -- much like stocks, bonds and real estate. The reason: Art can juice a portfolio's returns and lower the risk.

For years, private banks, such as those run by J.P. Morgan Chase & Co., Citigroup Inc. and Bank of America Corp., have offered wealthy clients interested in art a variety of services that helped to build their collections, ranging from market research to lending against the value of a portfolio of art so that clients could buy even more art. They typically didn't -- and most still don't -- approach art as an asset class to diversify a portfolio of investments.

Now, a growing number of art-investment funds aim to offer investors an opportunity to acquire a stake in a portfolio of artwork, much like a portfolio of stocks. Fernwood Art Investments plans to launch funds early next year that will buy, own and manage a broad portfolio of art for wealthy investors. Similar funds in the U.S., Europe and elsewhere, such as the United Kingdom's Fine Art Fund, are now raising hundreds of millions of dollars for the purpose of investing in everything from American masterpieces to porcelain and Chinese antiquities.

>Also on the horizon is a so-called fund of funds created by ABN Amro Holding NV that will spread investors' dollars across several of the new art-investment funds. The Dutch banking giant expects to introduce the fund early next year, and is even considering launching its own art-investment fund. ABN Amro also recently launched an art-advisory group, like those offered by other private banks, for its high-net-worth clients.

The move to art is just another sign that investors are redeploying money away from stocks, bonds and cash accounts, and into various hard assets ranging from timberlands to works of art -- items that are so-called stores of value. Adding to its appeal, art has proved to be largely noncorrelated with Wall Street, meaning that prices move independently from stocks, providing a measure of balance to a portfolio.

The idea is that because the art market "is highly inefficient, there is substantial opportunity to outperform through active management of a portfolio of art," says Bruce Taub, chairman of Fernwood. "Over the long term, the financial trend is that art goes up with the economy."

Art is substantially more volatile than stocks. Losses, though not nearly as well-publicized as the gargantuan gains, happen frequently. David Hockney's 1966 work "Portrait of Nick Wilder" sold in 2002 for $2.87 million, and then again in 2003 for $500,000 less. Monet's 1906 "Water Lilies" sold for $18.7 million in 2002, down from nearly $21 million a few years earlier.

A new breed of art investors, though, is applying portfolio practices typically found on Wall Street to paintings and other works. Instead of basing a stock's future value on expected earnings growth and cash-flow models, they're trying to value art by examining factors ranging from interest-rate movements to statistical models that dissect the rates of return for a particular artist's body of work compared with his or her peers. Some are even measuring the "liquidity" of an artist by examining how many works come up for sale and how many actually sell.<

These days, investors have several indexes to help them track the performance, or value, of art as an asset class. The most quoted is the Mei/Moses Fine Art Index, compiled by Jianping Mei and Michael Moses, business-school professors at New York University. That index ( www.meimosesfineartindex.org) is based on repeat sales of the same paintings, drawings, watercolors and sculpture. It currently captures about 75% of fine-art auction sales, and when the index adds postwar and contemporary art to the mix in January, it will represent between 90% and 95% of all auctioned art. The MEI/Moses index shows that art appreciated by a compounded 12.06% annually from 1953 to 2003. That's in line with the Standard & Poor's 500-stock index, which, with reinvested dividends included, posted gains for the same period of 11.65%.

Without question, numerous works have dished up returns even Wall Street envies. Picasso's "Boy With a Pipe," for instance, previously sold in 1950 for $30,000, meaning that in the intervening 54 years it posted compounded annual gains averaging more than 16%. But the painting "Fishermen," by contemporary artist John Currin, which sold earlier this year for $1.4 million, had a 101.5% annualized gain from the $85,000 sales price just four years earlier. Those figures are based on the paintings' so-called hammer price, which excludes the commission. Add back in commissions, which can be 20% or more of the price, and the shipping-and-handling costs, and the returns suffer.

But the indexes that investors use to gauge the market can be misleading. They capture only auctioned art -- and an estimated 50% of all sales happen privately, in a market where verifiable details are generally nonexistent. Thus, art pricing is incomplete. Worse, price changes in an artwork often take decades to occur -- assuming they happen at all, since many pieces are donated to museums or kept in the family. All this makes valuing art accurately nearly impossible for investors.

Art data being collected in recent years are making analyzing the returns of art more investment-like. Investors can dissect repeat sales of a particular work or of an artist's body of work and "get a good feel for how that artist has performed over the years" as an investment, says Prof. Moses of NYU. "If you can say, for instance, that over 80% of Picassos sell at market, and you can track the returns those sales have generated, you can make some general inferences about the market for Picassos."

Van Sabben Poster Auction 34

If one could go into a street plastered with posters from allover the world, one would soon notice that the posters from Poland are exeptional and stand out from the rest. Before Polish poster design matured and formed its national character, it evolved and throughout its development, built upon the heritage of almost all the new directions of the early XX-th century art.

The beginnings of Polish poster art date back to the 20's of the last century when artists drew inspiration from traditional Japanese woodcut and Art Nouveau. Early posters designed by contemporary artists resemble paintings reproduced on paper and only aspire to an independent discipline which uses concise and graphic images. However, in the 30's, thanks to designers mainly coming from Warsaw's architectural office, likeTadeusz Gronowski, Jerzy Hrymewiecki and Stefan OSiecki, posters gained new, short and concise form. Following the Art Deco style, light and ingenious posters with their own architectural typography gain worldwide recognition. The development of the Polish poster, mainly In advertising, was brutally stopped by the outbreak of WW II.

After the year 1945, in a new situation with Poland under Russian influence, poster art was seen as an ideal tool to transmit new political contents, A poster, in a simple or almost photographic way, was meant to show the direction Imposed by red decidents. In the mass of literal and flat propaganda posters, exeptlonal pieces appear. Artists like Tadeusz Trepkowski and Henryk Tomaszewski fight for the independence of poster art. Their designs tell the story using metaphor, Often the content can be read in many ways, sometimes different from what the communist authorities would like to see. Camouflaged symbolics express distaste for the Soviet regime. The year 1956 brings political system liberalisation and in the poster discipline it IS allowed to move away from the only acceptable art direction, socrealism.

After the year 1945, in a new situation with Poland under Russian influence, poster art was seen as an ideal tool to transmit new political contents, A poster, in a simple or almost photographic way, was meant to show the direction Imposed by red decidents. In the mass of literal and flat propaganda posters, exeptlonal pieces appear. Artists like Tadeusz Trepkowski and Henryk Tomaszewski fight for the independence of poster art. Their designs tell the story using metaphor, Often the content can be read in many ways, sometimes different from what the communist authorities would like to see. Camouflaged symbolics express distaste for the Soviet regime. The year 1956 brings political system liberalisation and in the poster discipline it IS allowed to move away from the only acceptable art direction, socrealism.

|

Huge state enterprises and theaters become the new patrons of Poster Art. Paradoxically, the restrictions imposed by the authorities allow the poster to flourish. Many artists of this period try to explore new solutions and directions. Posters quickly become a bastion of the New Art, Young and ingenious designers like Roman Cieslewicz, Wiklor Gorka, Jan Lenica, Waldemar Swierzy, Jozef Mroszzak and Wojciech Fangor, to name a few, join the group of older, already established artists. They treat this media as a work of art. Posters, which are unusually painting-like, are strongly linked to the Polish tradition, rich in means of expression, wit and intelligence.

A golden period from about 1955 till 1965 brings the most admired works. Foreign critics will soon call this phenomenon 'The Polish Poster School'.

In this auction a few posters from this period will be auctioned.

Jewish Posters In Poland

By Richard McBee

Posted 1/8/2003

After the war, Poland was ruled by a Soviet dominated Communist state, the Polish People`s Republic. Paradoxically, in the 60`s, 70`s and 80`s there were periodic exhibitions, performances and plays of Jewish subjects even though there were almost no Jews left in Poland, especially after a further expulsion in 1968. Posters specially created for each occasion announced these events. In a recent exhibition of fifty Polish Jewish Art Posters at the Consulate General of the Republic of Poland in New York, they present us with an amazingly creative outburst of Jewish art done by non-Jews for an audience who, for the most part, had never even seen a Jew.

Under the repressive Communist regime, there arose an entirely new cultural phenomenon, the Polish School of Posters. Before the war, there was a bustling business in posters of all kinds: political, sports, theater, health and, of course, performances. But those posters were strictly commercial broadsides to sell or advertise. Now, under Communism, posters were seen as an essential tool of propaganda to promote social causes and cultural events. Like all manner of art, they were tightly controlled by the state and yet also widely subsidized. The Warsaw Academy of Fine Art taught and promoted poster design, elevating simple design into a fine art form cumulating in the 1960`s and 1970`s. The Polish School of Posters came to rival the great age of poster art achieved in France of the 1890`s in fine quality and graphic invention.

Poster Art was encouraged in art collages and in national poster competitions throughout Poland. As a well-recognized profession, it attracted graphic artists, illustrators, sculptors, painters and photographers. A major group of "Cyrk" or Circus Art Posters emerged that cleverly embedded dissident messages in increasingly surreal and inventive images. All of the artists discussed here (with the exception of Gorowski) were part of this highly creative group. Their Cyrk posters are always wonderfully inventive, but it seems to me that the Jewish works reveal a special probing insight and questioning singular to this group. Perhaps the most surprising element of these posters is that under the repressive patronage of a Communism State, Polish artists managed to create a complex body of poster art about Jews, Jewish culture and its place in Poland. After 1989, and the introduction of a free market economy, poster art became increasingly commercial and the golden age of the Polish School of Posters slowly came to an end.

The creation of Jewish art without Jews in Poland 20 to 30 years after the Holocaust is perplexing, to say the least. What was occurring here?

I have no easy answer except that these posters exist, created as works of art to advertise cultural events, at least as puzzling as the works themselves. The intent of the non-Jewish artists, subsidized by the Communist State, is unknown and perhaps unknowable. The intention of the creator is always a problematic element in the meaning of any work of art and these are no different. In the final analysis, we must let these intriguing works speak for themselves.

Sholom Ansky`s play "The Dybbuk" summons images of the Jewish supernatural; anguished souls unable to find rest because of unresolved conflict. The original story tells of a pair of children betrothed at birth by their parents. Once they grow up, they meet and fall in love, but their marriage is thwarted by her greedy father who meanwhile pledged the girl to a wealthy suitor. The boy desperately tries to win her, but dies in the attempt. His soul, unable to find rest, becomes a dybbuk and possesses the girl`s body and can only be removed by an exorcism.

A poster made in 1975 by Marian Stachurski depicts the besieged couple rendered as a kind of woodcut image surrounded by stark cemetery and headstone shapes. The graphic contrast between the warm human image of defiant love and the cold finitude of the grave underlines one of the central motifs in the play. The couple, Leah and Khonnen, stand united in love against the cruel realities of life and even death.

The history of the Jews in Poland from 965 to 1990 is the subject of "Diaspora," a poster promoting a documentary film by director Leopold R. Norwak. The haunting simplicity of legions of footprints stretching out before us into a shadowy darkness summons the vast generations of Jews who made Poland their home and the tragic end of that legacy. In the middle of this image of Jewish travail is a cutout figure of a traditional Jew casting a long shadow that somehow evokes the still visible effect the Jews have upon Poland, the country of their Diaspora.

"Requiem" is the title to the poster by Leszek Holdanowicz. It announces a documentary film that is a Requiem for the Five Hundred Thousand. The exact subject of the film is unclear and yet the image and text reverberate with historical emotion. The word requiem is Latin for "rest" and is the first word in the Roman Catholic Mass for the Dead. Here it is combined with the quintessential Jewish symbol, the menorah, and perhaps addresses the sorrow and regret felt by the Poles as they began to face what had happened and what they had done.

Above a starkly simple seven-branched menorah seven hands raise up flame-like gestures in a haunting supplication. The only way any people can revisit its past is through it own cultural forms, and in Poland the language of sin, guilt, and forgiveness is deeply embedded in the Church. The introduction to the Requiem Mass intones; "Grant them eternal rest, O Lord, and may perpetual light shine on them. A hymn becometh Thee, O G-d, in Zion: and a vow shall be paid to Thee in Jerusalem. Hear my prayer." As strange and unnerving as it seems, a requiem for the murdered Jews might not be out of place.

The complexity of Polish-Jewish history and the current inexplicable fascination with it, is one motif that runs through many of these posters. Mieczyslaw Gorowski"s "Star of David" expresses a multitude of mixed emotions and conflicts as a Magen David pushes through a fabric, perhaps of Polish society, and reveals an eye peering out. The eye is the window of the soul, here of the Jewish people, and seems to be struggling to see and be seen but for the oppressive hand attempting to close down the flaps of the star.

Here the artist has encapsulated the struggle of the Polish people with their Jewish past. The poster promotes Jewish culture as it simultaneously expresses the contradictions and struggles that the very notion of Jewish culture evokes in Poland.

The past is not so easily forgotten nor forgiven in these graphic works that present a brilliant collection of unsettling and penetrating images reaching us from a unique moment in Polish history. It is the struggle with that history and the evolving Jewish culture in Poland today that these art posters, utilizing the simplest of texts and elemental symbols, so successfully engage and challenge our preconceptions about Poland and the Jews.

The Polish School of Posters; Polish Jewish Art Posters Contemporary Posters; 115 Central Park West, NY, NY 10023; (212) 724-7722; Many examples on website; www.contemporaryposters.com;

Richard McBee is a painter of Torah subject matter and writer on Jewish Art. Please feel free to email him with comments at rmcbee@nyc.rr.com.

Dybuk (1975), original Polish Art poster by Marian Stachurski. |  Diaspora (1990), original Polish Art poster by Mieczyslaw Gorowski. |  Requiem (1963), original Polish Art poster by Leszek Holdanowicz. |

Dybuk (1990), original Polish Art poster by Andrezej Pagowski. |  Star of David (1989), original Polish Art poster by Mieczyslaw Gorowski. |

| All images Courtesy of Contemporary Posters, Inc. | |

© Copyright 2001, The Jewish Press Inc. (ISSN 0021-6674)

All CYRK posters

All CYRK posters